I have a rather well-documented history as someone who never went camping as a kid. Between my single day as a Cub Scout, when a chocolate cupcake pointed the way to a lifetime appreciation of more serious pastries, to a week-long family canoe trip with my new wife in the Canadian Boundary Waters, there was a two-decade hiatus from life in a tent.

I guess my haphazard trip with a buddy to California back in 1976 is worth mentioning, or maybe not. It was a completely unplanned fortnight with a Triple-A Road Atlas and two pup tents. Those tiny orange domiciles were set up for the first time in Yellowstone National Park, secured between trees with a tangled spiderweb of my mother’s old clothesline in mid-September temperatures that we really hadn’t considered. We had no sleeping bags, but I did have a system of pulleys to loft our provisions, because, well, bears. And even the bears laughed at our ridiculous setup. It looked like we had been trapped in a snare.

Fast forward to somewhere in the 1990s and picture me as an adult Scout leader, attending meetings of the local BSA Troop 78 in Lincolnshire, Illinois. My son was rapidly collecting merit badges on his journey to the rank of Eagle, unaware that I was a Scout-shirt-wearing, complete fraud. I had just volunteered to lead the annual two-week-long expedition to MaKaJaWan summer camp in the Northwoods of Wisconsin.

“Your what hurts?” I quipped. No one laughed.

“MaKaJaWan,” responded our troop general, or whatever he was called. “You’ll have help,” he promised.

I found myself the leader of a small team of fathers, all of whom had previous experience leading this mission, all smiling at their good fortune at having drafted a sucker like me to do the recruiting and logistical coordination necessary to haul a dozen highly energized lads four hours north, through an actual Indian Reservation into a place I’d never been, never seen, and that was undoubtedly populated with mosquitoes, fish and well, bears. That's a rather long sentence, but I think it conveys my growing anxiety.

The adults met aside from the general scout meeting to bring me up to speed, hand me reams of documentation, and unload a rapid-fire brain dump of everything they felt I needed to know.

“Ok, we have the large three-man tent, we can set that up in a central location…” one began.

“Hold on,” I said, with surprising emphasis. After all, I was the leader.

“I’ll do this, but it’s on my terms.” I continued.

They looked surprised, but compliant, listening.

“You can sleep however you want, but I will be in my own tent, in a location of my choosing, on a queen-sized air mattress,” I said.

“And I’m only going for one week, not two. I can’t do two,” I said, as if my schedule, and not my willingness to endure this ordeal was the limiting factor.

The team was structured to spread adult oversight of the boys between the two weeks, with additional help from fathers who had schedules even more limiting than my own. They would come up toward the end of week one and stay over the weekend, bridging the change of command. It was even agreed that I could command week two. This pleased me greatly. All the heavy lifting would be done by the day-one dads. I just had to take over and coast to the finish line. How hard could it be to pack up and head home after a week in the wilderness?

And then there were the moms. Granted, there were several who would have been much better at my job, but most chose to keep the home fires burning. They had gathered for our early morning departure, some with enough collective angst to raise the Titanic. The first-time scouts, their babies, were gingerly handed over with enough neatly packed luggage to, well, voyage on the Titanic. More experienced mothers had been looking forward to this week of summer respite for so long that their tears were those of joy, and they nervously checked the time as if our departure might be called off at the last minute for some unexpected reason.

But one late arrival turned into the church parking lot on two wheels, and if a group of adults and children had not been coalescing mid-asphalt, she might not have had the decency to stop the car in order to eject little Randy. Be gone, little Randy, my time is here, and yours is there. Poor Randy stood alone with his bulging black plastic yard waste bag of belongings. We felt sorry for him for a few minutes. A few blessed, silent minutes, while he sized us up and identified our weaknesses like a predator that can smell fear. He dutifully walked up to an adult and handed over a clear gallon-size plastic baggy, stuffed with pill bottles and hastily scribbled notes. The burning rubber from his mother’s tires hung in the broadening dawn daylight. Leaders exchanged glances and directed the last passenger to his designated transportation.

We headed out in the morning mist, sucking coffee to wash the webs from our brains and to ensure wakefulness for the long drive ahead, a convoy of fresh and spirited campers ready to make memories and acquire new skills. Kids didn’t have cell phones at the time of this trip. There was one early model flip phone per car, and I drove a GMC Envoy equipped with OnStar. I could call by satellite to the dark side of the moon from the depths of a cave. Well, not really, but my car became the phone booth later in the week when emergencies required contact with parents and there was no cell signal in camp. It turned out I had some unanticipated value after all!

By the time we began our passage through the Menominee Indian Reservation, we had been in the car for five hours. The four-hour trip was punctuated by multiple rest stops and breakfast, organizational exercises that revealed behaviors that would be perfected in the coming seven days. As we entered the dark woods and winding roads of “The Res” I began to ruminate about our fate should we break down and need assistance. Would that be the moment when what had gone around came back around? Or would we be ignored?

It was eerily quiet, beautifully serene, and my first time spent in an area designated as sovereign, self-governed, a country within our country. I thought back to stories of pioneer children abducted by tribes and raised as their own. How might Randy turn out? And what would he be named? "Crazy Horse" was taken, and though he had the energy chiefs possessed during earlier centuries, his leadership potential was not great. Anyway, onward to camp. We were almost there and the blackening sky heralded our first storm of the week. Names would be considered later.

I will never forget the gleeful reception we received upon our arrival at the beginning of week two, and the giddy group of stinking, mosquito-mangled adult executives that almost literally threw the log book our way as they ran to their cars, muttering something about two kids in particular.

“It rained quite a bit,” they said over their shoulders. And, “Watch Hank around the fire. He needs a little extra support. Keep him and Barry apart”

I lugged our family tent through the West Campsite called Fremont, undoubtedly named for John Charles Fremont, a famous nineteenth-century army captain and explorer of the untamed West. Up a path I had located upon arrival to a secluded hilltop, I took several loads of my stuff, eventually struggling with my fully inflated, unnecessarily large air mattress, whiplashing myself as I pushed reproachful branches out of my way, enduring the hoots and hollers of the team, and eventually shoving the beast into what became affectionately known as the “Taj Mahal.” I caught my breath, somewhat satisfied with my progress. Frontier Fremont never had it this good. The week, and my trip to the camp proper, both went downhill from that point forward.

Flight attendants instruct passengers to put on their own oxygen mask before trying to help others. With that philosophy in mind, I began the assembly of the "Taj." By the early '90s, our family had been on yearly camping trips, generally weekend events, and we owned a pretty, beige and brown old-style nylon tent that we partitioned into adult and child compartments. We carefully cleaned, folded, and stowed our faithful shelter after each use. It was about to get a real workout. Ordinarily, my wife, daughter, and son would share this special place. Did I mention that my son was part of our Scout cohort? He was at an age where he wanted as little as possible to do with me, and I fully understood. A subtle nod in my direction felt like a handwritten three-page letter by mid-week.

From the depths of the woods at the top of my small hill, the other adult leaders were treated to a virtual carillon of clanging metal tubes and some indelicate muttering. Setup could be accomplished by one person but was far easier with four. But it was home, and the illusion of safety, at least from mosquitoes, was comforting. I looked forward to nightfall.

Two cots awaited each tent-pair, also from the Great War, and the carefully tied-open flaps at the front of the tent stood like the waiting mouth of a Great White. It was the portal between light and dark, the visible and invisible, into which the boys shoved their belongings and began the process of recreating their bedrooms at home, the piles, the culture media that would incubate in the summer heat, mold and tears over the duration of their stay. With a stunning clap of thunder that rolled over the lake and across the campground, the rains began.

* * * * *

Before becoming the summer camp coordinator, I volunteered as a driver, bringing a carload of boys to camp. It was a good introduction to the beautiful Northwoods setting, and helped me visualize where my son would be living for the next week. The round trip was an all-day affair, about five hours each way, just two hours south of Lake Superior.

Weather in Wisconsin can be quite changeable and violent. Such was the case in July of 2019 when a fast-moving derecho destroyed much of the camp, snapping like twigs trees that fell with the power of wrecking balls on tents and buildings. Of the 350 people in camp, only one sustained an injury. It could have been so much worse.

I witnessed an approaching storm on the day I drove the scouts. We arrived just in time for lunch, and Troop 78 headed obediently down from our site to the dining hall. I had hoped for a hug goodbye from my little boy, but was immediately reminded of his status as young man among parentless peers, and of their camaraderie as they marched resolutely toward lunch. I said goodbye, have fun, and got a nod in return. And then I looked up above the tree line.

The sky was black. Not the dark gray of an ordinary approaching thunderstorm, this looked like space itself was collapsing Earthward just north of camp. My stomach turned. I watched the boys, saw them grow smaller and eventually disappear behind a screen of trees, then headed to my car as a cold rush of wind flowed in a torrent down the gravel road out of camp. As I headed out, I glanced in my rearview mirror and saw only blackness behind me. Leaving felt irresponsible, reckless, but necessary. I trusted those with experience to keep the kids safe.

It was not my last experience with Makajawan weather. Conditions in the camp were seldom the same from year to year. One July we would be chilled and plagued with mosquitoes. Another we would sit out of the blistering sun in the shade within our campsite, trying not to move, with cool wet rags on our necks and the growing fatigue that became the hallmark of heat exhaustion. The boys seldom complained, at least until they developed headaches or began throwing up due to dehydration. It was hard to keep track of individual water consumption during the between-meal hours in which they pursued badges and learned new skills.

The daily agenda within the camp was a blessing. Flag raising, three meals, flag lowering, and then time in Fremont around the campfire. It was clear that the younger scouts relished the time after dark. They were mere babies, just out of Cub Scouts, running on adrenaline to the point of near collapse, often as evidenced by growing misbehavior. The older scouts tended to cluster together. As they aged, they became fewer, with those whose path to Eagle derailed losing interest in scouting altogether. It was a significant time commitment.

The first night in camp was a sheep-herding exercise for the leaders. Reminder after reminder to prepare for sleep went unheard. Possessions and hygiene items needed to be safely stowed, readied for morning. Eventually, one brilliant leader hit upon a motivating ruse that resulted in the near-immediate formation of a quiet, single-file line of young scouts.

“Hey everyone! Bears are attracted to toothpaste,” he said.

Wide-eyed, silent, and presenting plastic baggies of toothpaste and snacks, the youngest scouts assembled and were suddenly ready to hit the sack. Dream the dreams of men, oh you growing scouts. And please, use the bathroom before you do.

After a period of adult conversation, I headed off to my own accommodations. The illusion that a flimsy layer of nylon fabric provides, and the real barrier against moisture, mosquitoes, and whatever made the various scurrying noises in the woods, was a great comfort at the end of a long day. My place at the top of the hill ensured that I wouldn’t be the one to respond to cries in the night, requests to go pee, or other attempts to get attention by young scouts new to being away from home. I felt like Marlon Brando at the end of the river in Apocalypse Now. If the glowing solar LED torches available now could be had then, I would have posted two outside my tent door.

My gigantic air mattress was heavenly. The flannel liner of a wide-open sleeping bag and a light sheet were perfect on a mild summer night. And bears-be-damned, I pulled a large bag of plain M&Ms out of my duffle bag for a nighttime snack. I plugged my headphones into my MP3 player and listened to a soothing tale from Lake Wobegon as told by Garrison Keillor. This camping life was alright after all.

But several hours after the point at which I dozed off, the droning voice of Keillor lulling me into a state of relaxation that segued nicely into sleep, I was awakened by a new sound. I pulled my headphones off and listened. In the distance came the sound of surf gently rising and falling. Waves of percolating water, hissing as it retreated from the porous sand of a distant beach. But wait, waking self, that’s not possible. The waves were coming gradually closer, louder, beginning to sound more like an ominous roar. I envisioned a tsunami overtaking our campground, and in fact, the wind I had been hearing eventually reached us, the leading edge of a front that produced stunning lightning and a drenching downpour. The ground trembled beneath nearly simultaneous flashes of light and cracking explosions. Faults appeared in the illusion of safety within my nylon sanctuary, but the structure held and kept me dry.

As the worst of the frontal passage moved on, a gentle rain set in. And there on my hill, I drifted off to sleep again to nature’s white noise. In the temple of the North Woods, I was a guest. I had to learn to play by a new set of house rules.

* * * * *

The frontal passage that shook me from my sleep during the last week of July in 2002 pushed trees aside with a tidal wave of sixty-mile-per-hour winds. The storm was not tornadic, so scouts at Camp Napowan about a hundred miles south of us were told to shelter in their tents instead of relocating to the lodge. But an eighty-foot pine tree snapped and fell on a tent where one eleven-year-old scout was killed and another seriously injured.

We found out about this much later, but I tried to imagine making a phone call to inform a boy’s parents that in the lifetime of summers ahead, filled with thousands of scouts heading off to a week of harmless fun in the woods, their son would never again be one of them. I tried to imagine receiving such a call. House rules in the North Woods included the unexpected, and we would soon enough be making phone calls of our own, though none like that.

By mid-week, the scout I have called “Randy” came out of the medication-induced stupor his mother engineered the morning she handed him off to us on our way to camp, and he was now in full-blown attention-deficit hyperactive meltdown. We tried to sort out his bag full of pills on yet another of our troop’s trademarked spreadsheets, to no avail. Had he been taking them according to instructions? Was the heat causing a chemical imbalance? We just had to keep him from hurting himself or others.

“Put down the axe, Randy!” I yelled when I followed him and several other boys into the woods. The gleam in his eyes and on the edge of the sharpened tool was doubly disturbing. He was not trained in its use. He was too young. And I suspected he was curious to see if human limbs yielded different results when chopped than those of a tree.

“I’m going to call the constable!” shouted another adult, the father of a child known to exhibit Asperger's symptoms. He ensured his child’s safety by attending along with him.

A constable? I thought to myself. Are we in England?

So, now we had to calm down children and adults. The weather, the woods, and the wild ones were wearing on us all.

In a moment of personally antisocial enjoyment, I called Randy aside just before dinner one evening. It was cookout night, and a long row of huge camp grills had just been lit. Bright orange flames leaped three feet in the air along a line of cooking surfaces perhaps twelve feet long. Set against the lake as a backdrop it was quite dramatic and also very picturesque.

“Hey Randy,” I called, “You want your picture taken with fire in the background? It’ll be really cool!”

His eyes widened, illuminated from within by his own demonic magma and reflecting the flames dancing above the grills.

I positioned him in front of the cooking area, Hellish flames behind and above him.

“Smile!” I said. He complied, ear to ear.

It was not only the longest he’d stood still all week, but it gave him immense pleasure when I showed him the digital image. It was a compositional masterpiece and the photo with which I came to remember him. Randy the devil.

Randy needed attention, not only to keep others safe but for his own sake as well. We started to feel sorry for him. He was our special camper. Infuriating at times, but sweet at others. While all of the other kids naturally paired up or formed small groups, Randy remained the outsider, despite our intervention on his behalf. And then came the incident.

In the dark, on the way back from the bathrooms to Fremont, a small group of younger scouts started goofing around on a gravel road. A rock was thrown and a scout was hit in the head. Randy!

We discussed what Randy’s punishment would be. We huddled in our now familiar circle of leaders and spoke in hushed tones. Do we call parents? Send scouts home?

The participants were summoned and appeared, looking downhearted in front of us. It was then that we discovered that Randy hadn’t thrown the stone. He was the victim!

We patched him up, quickly adapted to the emerging situation, and sent the scouts to bed with the knowledge that parents would be called the following morning. My car, with its satellite phone service, became the phone booth. Even at the time, I wondered if it was an overreaction to alarm parents with a call and suggest that they could make a five-hour drive to retrieve their son if they chose, but the adult leaders with much more experience than mine were convinced it was necessary.

By the following evening, the event seemed like a distant memory, no scouts went home, the week was winding down and the black, rain-washed night sky, oh my, it was full of stars!

* * * * *

We settled into a camp routine so well established by capable personnel and years of experience it seemed to be almost on autopilot. By mid-week the adults were becoming a bit restless, looking for things to occupy their time other than updating spreadsheets during the several-hour stretches twice daily when scouts were busy with badge-earning activities.

Motivated by relative boredom, one adventurous leader signed up to compete along with the scouts in a mini triathlon comprised of swimming, canoeing and a run through the woods. I had always been an avid swimmer, at one time the owner of a rather large in-ground pool. I routinely swam a mile, though 125 lengths of the pool became almost immediately monotonous. I elected to sign up only for the one-mile open water swim. The lake was one eighth of a mile from shore to shore. Four round trips completed the challenge.

The previous night was something of a high point during the week. Shortly before we all turned in, I went to the bathrooms down near the parade field. The sky was particularly clear, dark and filled from tree-line to tree-line with stars more dense than I’d ever seen before. The Milky Way became real for me that night, made possible by the complete absence of ambient city lights or local incandescent light pollution. And then, I noticed something else. At some indefinable point between me and the starfield was a shimmering gray-green curtain, slowly drifting and fluttering and hard to pinpoint. I watched for a while before realizing that I was being treated to my first ever view of the Northern Lights. The Aurora Borealis! I had to tell the kids!

I scurried up to camp and roused a small group of recently retired adults and scouts. Some were beyond caring, comfy in their sleeping bags and within canvas walls. But a small bunch of us trekked down to nature’s planetarium and stood silently staring straight up. Silent, that is, until from the darkness behind me I heard a young voice exclaim,

“I will NEVER forget this!”

How do you put a price on that?

Of course, high points are often followed by low points. The boys had been practicing flag folding all week, readying themselves for our turn of honor on the parade field at morning flag raising. When the time came, our small contingent processed down to the flag pole, while the rest of us waited along with a large encircling ring of all the troops in camp. We were in our best scouting gear, especially those doing the honors. In coordinated military fashion our handful of designated flag bearers marched to the base of the pole, unraveled the secured line and readied the clips to attach and raise the flag.

No sooner had they begun to hoist the stars and stripes into the air than I heard a gasp from two of our adults and numerous others around the field. The flag was being lofted as the stripes and stars, upside down, the universal sign of distress. There was really no way to remedy the situation from where we stood. Hollering would have been bad form. The mistake was quickly spotted by those much closer, the flag lowered and reclipped, then properly raised and secured. You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression. Onward to the dining hall where a breakfast of pancakes and sausages took the unpleasant taste of shame and humiliation out of our mouths.

Later that day came the triathlon and the one-mile swim. They were part of the waterfront Olympics, an all-day event. It was my chance to show what I was made of, though the lake water was undoubtedly cooler than my pool water had ever been. But I eased myself in, put on my goggles and prepared to dazzle everyone with my freestyle. Kayaks and canoes lined up across the lake, spaced evenly apart with life jackets and floatation devices at the ready, should assistance be required.

If you’ve never tried an open water swim, it is at once a head trip and a disorienting challenge completely different than laps in a pool. Lake water is dark and opaque. There are no telltale lap lanes visible in clear blue depths beneath you. And there’s no knowing how much distance separates you from the bottom of the lake, or what might be lurking there. Also, unlike a short lap, the natural extra power in your dominant arm tends to pull your body off center, veering away from the straight line you intend to swim. Course correcting is a major inconvenience. All of this combines in a psychological cocktail that can result in an endurance-crushing anxiety attack that, in my case, left me gasping for air and asking for help by the middle of only my second crossing.

“Are you serious? You really want one?” asked the man in the kayak, holding out a float.

“Yes!” I said, twice, grabbing the device and paddling back to the starting point.

At this point, I wasn’t swimming the mile, I was exiting the lake. Add that to the list of things I wasn’t made of.

One final campfire, a last night sleeping under the stars and it was time to go home. I would have other fond memories with the scouts but nothing quite like summer camp. Subzero campouts in frigid winter cabins held their own charm, huddled around a blazing woodstove playing poker and wagering M&Ms with my son and four of his teenaged friends. Scouting was a temporary condition for some, a life altering springboard for others. One young man is now camp director at the rebuilt Makajawan, and others have pursued careers in Environmental Science, scattered to the corners of this spectacular country.

My own son built upon the skills he acquired on his way to Eagle. He spent several years in the Peace Corps in remote parts of Guatemala where the seasonal monsoons rattled the tin roof of his cinderblock room in a much less quiet and comforting way than the gentle rain on the roof of my tent in Fremont. He now goes on solo backpacking treks all over the world, hiking through stunningly beautiful locations, testing his skills under the stars, alone on the land, and with his thoughts, perhaps thinking,

“I will never forget this!”

😎

If you like fiction and you're in the mood for over 50 short stories, please consider buying "Natural Selections," at Amazon.com.

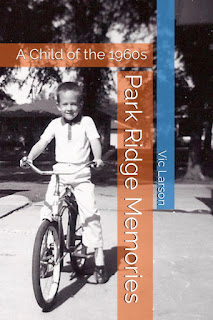

Or if you'd prefer seventy non-fiction stories inspired by a town in Illinois, please consider buying Park Ridge Memories also on Amazon. Click on the image below.